Porting your LaTeX package in LaTeXML

Summary: I’ve starting porting the knowledge package in LaTeXML. This entry explains the beginning of this journey, in the hope of helping others to port their LaTeX package in LaTeXML.

The goal of this document is to supplement LaTeXML’s manual with a concrete simplified example of porting a LaTeX package in LaTeXML. You are hence encouraged to read Chapters 1 to 4 of the manual before reading this entry.

A toy version of knowledge

For the purpose of this entry, I will describe an extremely simplified version of the LaTeX knowledge package, called toy-knowledge, and that I will then port in LaTeXML. The goal of knowledge is to easily insert internal hyperlinks: this way, when the reader encounters a technical notion (say in a scientific document), then they can simply click on it to see its definition.

In toy-knowledge, we will use the following syntax to indicate that “some string” is a technical term that should be clickable.

\kl{some string}

This command should print the text “some string”, and produce a link to its definition. The definition of “some string” should be indicated with the following command.

\intro{some string}

The last feature we want to implement is synonyms: you want to have a way to say that “foo” and “bar” are synonyms, so that if you write

\intro{foo}

\kl{bar}

then the link of \kl{bar} will actually refer to the definition

\intro{foo}. This will be permitted by the following syntax.

\knowledge{foo}{notion}

\knowledge{bar}{link=foo}

Every knowledge (something that is either the source or destination of a link)

must be declared using the \knowledge command. We can either identify it

is a new notion with the notion keyword, or make it a reference to an already defined

notion with the link=… keyword.

Just like in the original knowledge package, we would like to allow the user to potentially define the knowledges after using them, and so

\intro{foo}

\kl{bar}

\knowledge{foo}{notion}

\knowledge{bar}{link=foo}

just produce exactly the same document as

\knowledge{foo}{notion}

\knowledge{bar}{link=foo}

\intro{foo}

\kl{bar}

A short introduction to LaTeXML

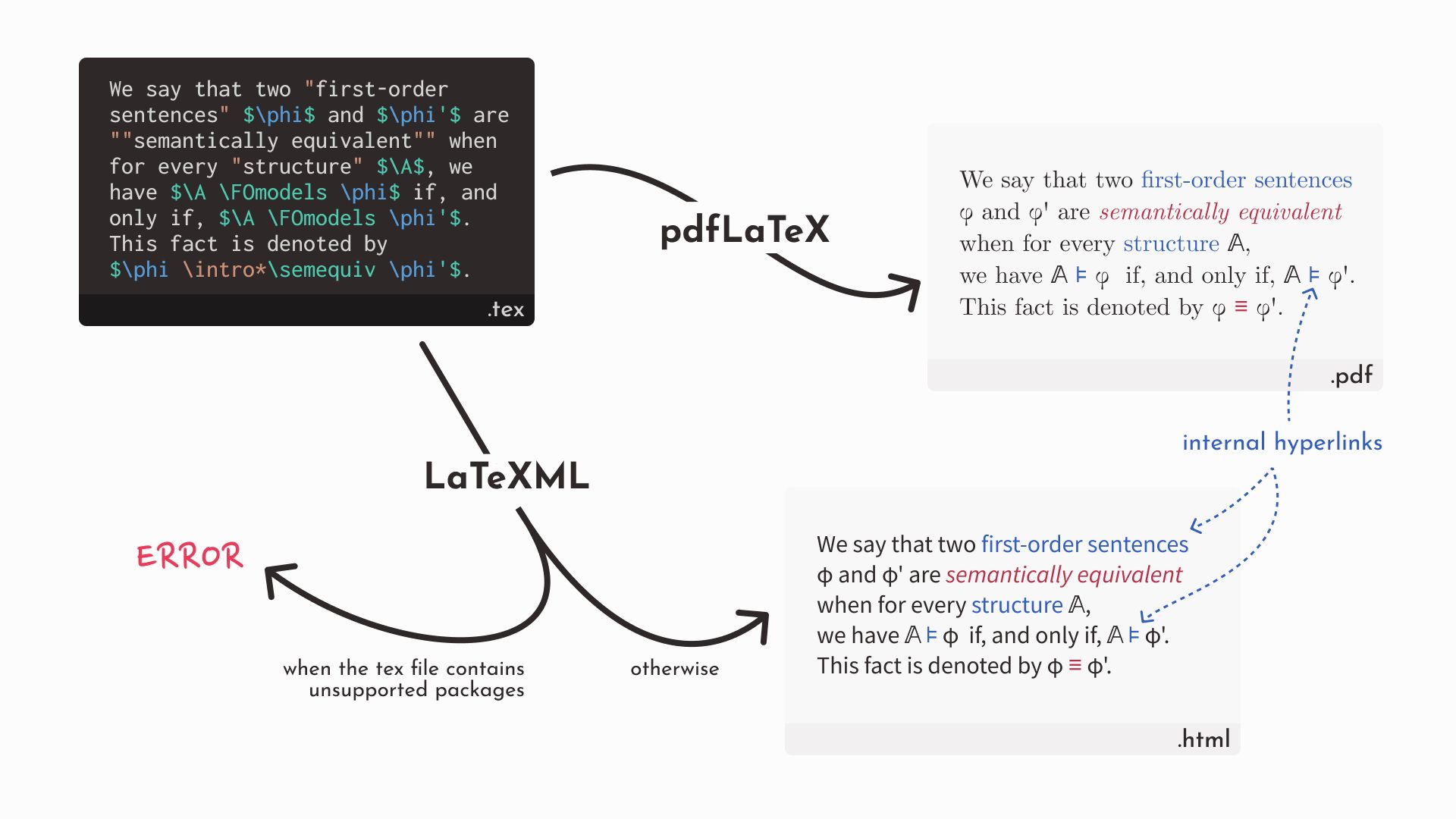

LaTeXML is a LaTeX-to-HTML transpiler. The difficult part in the job is to actually

produce XML from LaTeX (with latexml): once you’ve generated the XML, you can then easily generate HTML5

or alike (using latexmlpost).

The LaTeXML architecture [source]

To port toy-knowledge, we will work on LaTeX-to-XML transpiler latexml, in other words, we

will not touch the post-processing phase.

The differences phases of LaTeXML can be summed up as follows:

- The mouth converts the input LaTeX into a list of tokens. This is the first step of

parsing LaTeX. A token is usually a character (somethings a string) together with some

semantical information on its nature. Examples of tokens include

T_BEGINandT_END, representing{and}respectively,T_LETTER('z'),T_OTHER('('), orT_CS('\textbf'). “CS” stands for control sequences: these correspond to LaTeX commands, without their arguments. - The gullet expands the tokens and does parsing. Expansion is the LaTeX process

of replacing (or rather… expanding) macros. For instance, if you have a LaTeX command

then during the expansion phase, whenever you’ve used the command

\newcommand\foo{\textsf{foo}}\foo, it will be replaced by\textsf{foo}. - The stomach then takes care of the digestion, which is the process of transforming tokens into boxes and whatsits. Boxes represent simple elements (for instance a letter that should be printed), while whatsits are used to generate XML tags.

- The intestines take care of construction, which transforms boxes and whatsits into a document object model (DOM) that represents the syntax tree of your XML document.

- The rewriter allows you to define arbitrary rewriting procedures on this tree.

You could imagine things like

“if there are two consecutive

reftags with the same link, then merge them into single tag”. - Finally, the serializer simply serializes your tree: it converts the XML syntax tree into a linear structure, namely your final XML document.

Importantly, these phases are sequential document-wide, in the sense the whole document goes through the gullet before going to the stomach.

Perl

LaTeXML is written in Perl.

If you’re not familiar with this language, to be able to understand the code in the

rest of the blog post, you might want to know that it is dynamically typed, but

differentiates scalars ($) from arrays (@) and from hashes (% ; hashes correspond to what you might know as dictionaries).

Functions are called subroutines, and they receive their arguments in an argument array called @_.

Consider the following piece of code.

sub foo {

my ($a, $b) = @_;

my $c = $a + 2*$b;

if ($c >= 0) {

return $c;

}

return -$c;

}

printf foo(3, 4);

It defines that subroutine foo that expects two scalars as arguments, that we call $a

and $b. It computes $a + 2*$b, and returns its absolute value.

By default, Perl returns the value of the last instruction, so the last keyword return

could actually be omitted.

Porting toy-knowledge in LaTeXML

When?

As mention in the manual, to port our package, we will define a Perl module toy-knowledge.sty.ltxml

in the lib/LaTeXML/Package/ directory.

The first question is to identify at what phase we should deal with each command.

\klshould produce a link. In XML, this can be done with the<ref>tag.\introbehaves exactly as\kl, except that we want to specify the destination of a link rather than its source: we will use the<anchor>tag.\knowledgedoes not produce any XML tag. Rather, it gives us some information that we will use internally to resolve links. Moreover, we want this information to be handled before we’re processing the\kland\introcommands.

Given these constraints, it is natural to choose \kl and \intro to be

processed during construction: this is the phase where we actually produce

the XML. On the other hand, \knowledge can be processed during digestion:

this phase happens strictly before construction, but late enough that

we’ve already parsed the document.

LaTeXML comes equipped with functions that will precisely allow us

to handle these commands: DefPrimitive to deal with digestion,

and DefConstructor to deal with construction.

Next, we need to find a way to share information across the document: we will

need it since \knowledge will provide with information (synonyms) that we will want to

use later with \kl and \intro.

This can be done with AssignValue/LookupValue that essentially defines (resp. looks up the value of) a global variable

shared across the document. Rather than values, you can also have a global hash

with AssignMapping/LookupMapping.

So globally, here is what we want to do:

- During digestion, we want to handle

\knowledgecommands. We will store synonyms in a hash: its keys will be knowledges, and its value will be its parent knowledge (or itself if it has none). For instance,will produce a hash that maps “foo” to “foo”, “bar” to “foo” and “quuz” to “bar”. I propose to call this hash\knowledge{foo}{notion} \knowledge{bar}{link=foo} \knowledge{quuz}{link=bar}KL:knowledges. - During construction, we will produce XML

<anchor>tags. For\kl, they will be link source (meaning that they will have arefattribute, pointing to their destination), and for\intro, they will be link targets (meaning that they will have alabelsattribute).

The mapping of knowledges

DefPrimitive('\knowledge{}{}',

sub {

my ($stomach, $kl, $keyword) = @_;

if ($keyword->toString() =~ /^link=(.*)$/) {

my $link = $1;

AssignMapping('KL:knowledges', $kl->toString(), $link);

} elsif ($keyword->toString() eq 'notion') {

AssignMapping('KL:knowledges', $kl->toString(), $kl->toString());

} else {

Error('expected', 'notion or link=', $stomach, "Second argument of \\knowledge should be 'notion' or 'link=…'.");

}

return undef;

});

In its most elementary form, DefPrimitive takes two arguments

- a prototype, here

\knowledge{}{}, which means that whenever we encounter the control sequence\knowledge, we expect it to be followed by two arguments ({}) - a replacement code, which is a subroutine that takes the current state of the stomach and the parsed arguments

(here there are two arguments, that we call$klandkeyword). This subroutine will be executed during digestion, usually returns nothing (return undef;, although it could return Boxes or Whatsits).

Here, the replacement code does the following: first,

it tries to match the second argument to the regular expression link=(.*).

- If successful, it defines a new scalar

$linkwith the value of the first group ($1) of the regexp. in this context,$linkwill hence contain the argument, stripped of its prefixlink=. We then assign the value of$linkto the first argument in the mappingKL:knowledges. - Otherwise, it checks if the second argument is the string “notion”,

in which case, in the mapping

KL:knowledges, we map the first argument to itself. - Lastly, we raise an error, of type “expected”.

Note that this is executed at digestion, and so the arguments will have already been parsed: they are not strings,

but lists of tokens. This is why we need to use the method ->toString().

For instance, if the LaTeX document contains

\knowledge{foo}{notion}

\knowledge{bar}{link=foo}

\knowledge{quuz}{link=bar}

then the mapping ‘KL:knowledges’ will map “foo” to “foo”, “bar” to “foo” and “quuz” to “bar”.

Now, to deal with links, given a set of knowledges that are synonyms,

we want to assign to this class a unique identifier. Naturally, we choose the first notion of the class

that was defined. It can be computed by iteratively following the link. For instance, the identifier of

“quuz” will be “foo” since “quuz” links to “bar” which in turn links to “foo”, which has the keyword notion.

sub getIdOfKnowledge {

my ($kl) = @_;

if (my $link = LookupMapping('KL:knowledges', $kl)) {

if ($link eq $kl) {

return $kl;

}

return getIdOfKnowledge($link);

}

return undef;

}

All three scalars getIdOfKnowledge("foo"), getIdOfKnowledge("bar"), and getIdOfKnowledge("quuz")

will be equal to “foo”.

Inserting links

Now we simply need to produce refs and anchors from \kl and \intro during construction.

The syntax of DefConstructor is similar to that of DefPrimitive except that the first argument of the replacement subroutine

is not the stomach but the document.

DefConstructor('\kl{}',

sub {

my ($document, $kl) = @_;

my $klId = getIdOfKnowledge($kl->toString());

$document->openElement("ltx:ref", (labelref => $klId, class => "kl"));

$document->absorb($kl->toString());

$document->closeElement("ltx:ref");

}

);

This produces in the document, an XML tag <ref></ref> with two attributes:

- “label,ref”, which is set to the id of the knowledge,

- “class”, set to “kl”.

The content of the tag will be the argument of the

\kl{}.

For instance,

Some \kl{quuz} test.

will produce the following XML

<para>

<p>

Some <ref class="kl" labelref="foo">quuz</ref> test.

</p>

</para>

In fact, it can happen that $klId is undefined, which will happen it the LaTeX document did not

define the knowledge we are trying to use. In this case, we could want to still produce some valid

text, but with a warning. You would also like to ensure that this is processed in ’text’ mode (as opposed to ‘math’),

which can be done by adding the mode => 'text'.

DefConstructor('\kl{}',

sub {

my ($document, $kl) = @_;

my $klStr = $kl->toString();

if (my $klId = getIdOfKnowledge($klStr)) {

$document->openElement("ltx:ref", (labelref => $klId, class => "kl"));

$document->absorb($klStr);

$document->closeElement("ltx:ref");

} else {

$document->openElement("ltx:text", (class => "kl-warning"));

$document->absorb($klStr);

$document->closeElement("ltx:text");

Warn("ignore", "\\kl", $document->getElement(), "Undefined knowledge '$klStr'.");

}

},

mode => 'text'

);

Introductions are dealt with similarly, except that we produce <anchor> tags with labels.

DefConstructor('\intro{}',

sub {

my ($document, $kl) = @_;

my $klStr = $kl->toString();

if (my $klId = getIdOfKnowledge($klStr)) {

$document->openElement("ltx:anchor", (labels => $klId, class => "kl-intro"));

$document->absorb($klStr);

$document->closeElement("ltx:anchor");

} else {

$document->openElement("ltx:text", (class => "kl-intro"));

$document->absorb($klStr);

$document->closeElement("ltx:text");

Warn("ignore", "\\kl", $document->getElement(), "Undefined knowledge `$klStr`.");

}

},

mode => 'text'

);

An example

Consider the following LaTeX document.

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage[utf8]{inputenc}

\usepackage[T1]{fontenc}

\usepackage{toy-knowledge}

\begin{document}

A \intro{puma}, also called \kl{mountain lion},

is a kind of big cat.

\kl{Mountain lions} live in America.

Some \kl{undefined} knowledge.

\knowledge{puma}{notion}

\knowledge{mountain lion}{link=puma}

\knowledge{Mountain lions}{link=mountain lion}

\end{document}

Running latexml on it, together with the toy-knowledge.sty.ltxml binding we just defined,

produces the following XML document.

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

(…)

<document xmlns="http://dlmf.nist.gov/LaTeXML">

<resource src="LaTeXML.css" type="text/css"/>

<resource src="ltx-article.css" type="text/css"/>

<para xml:id="p1">

<p>A <anchor class="kl-intro" labels="puma" xml:id="p1.1">puma</anchor>, also called <ref class="kl" labelref="puma">mountain lion</ref>,

is a kind of big cat.</p>

</para>

<para xml:id="p2">

<p><ref class="kl" labelref="puma">Mountain lions</ref> live in America.

Some <text class="kl-warning">undefined</text> knowledge.</p>

</para>

</document>

Perhaps it is worth noting the anchor

<anchor class="kl-intro" labels="puma" xml:id="p1.1">puma</anchor>

which has an xml:id attribute: this is because LaTeXML automatically assigns an xml:id attribute

to every tag with labels.

In turn, using latexmlpost on this document will produce the following HTML code.

<!DOCTYPE html><html lang="en">

<head>(…)</head>

<body>

<div class="ltx_page_main">

<div class="ltx_page_content">

<article class="ltx_document">

<div id="p1" class="ltx_para">

<p class="ltx_p">A <a name="p1.1" id="p1.1" class="ltx_anchor kl-intro">puma</a>, also called <a href="#p1.1" title="puma" class="ltx_ref kl">mountain lion</a>,

is a kind of big cat.</p>

</div>

<div id="p2" class="ltx_para">

<p class="ltx_p"><a href="#p1.1" title="puma" class="ltx_ref kl">Mountain lions</a> live in America.

Some <span class="ltx_text kl-warning">undefined</span> knowledge.</p>

</div>

</article>

</div>

<footer class="ltx_page_footer">(…)</footer>

</div>

</body>

</html>

As expected, both mountain lion and Mountain lions link to puma.

Conclusion

Naturally the toy example given here could be improved. On the LaTeXML side, we could

look at latexmlpost to change the CSS and display the intro/kl with special colors

by using the classes kl, kl-intro, kl-warning and kl-intro-warning.

The trivial implementation of the union-find structure we gave for defined knowledges can naturally be greatly optimized. With our implement, there could also be circular links.

More importantly, I would like to conclude with a few things I learned during my last month working with LaTeXML:

- Always start by asking yourself at which phase (e.g. digestion v.s. construction) of the process you should work.

- If you don’t find enough details in the manual, check out the code: there are many helpful comments, and it is actually much more readable that I originally expected (once you get used to reading Perl).

- While LLMs are essentially useless at producing correct bindings, they are fantastic at pointing out which features/functions of LaTeXML you can use to achieve a specific goal.